Now Reading: What we can learn from the world’s vanishing cave dwellers

-

01

What we can learn from the world’s vanishing cave dwellers

What we can learn from the world’s vanishing cave dwellers

Nearly a decade ago, documentary photographer and National Geographic Explorer Tamara Merino was driving a camper van through the hot and seemingly desolate expanse of Australia’s Simpson Desert, when one of her tires blew out. The nearly 70,000 square miles of barren red dunes are not a place you want to have car trouble; summer temperatures push into the 120s, and water is scarce. Merino coaxed her van down the road and began to see signs of a town. But there was no one in sight, and the few buildings felt abandoned. Wandering the streets, she spotted a rudimentary metal cross on a hilltop. She scrambled up to take a look and found that a wide courtyard opened up below, forming the facade of an underground Orthodox church.

There are some 2,000 cave homes in the hills of Guadix, in southern Spain. Once used by the Moors to avoid religious persecution, they now house a community of over 3,000 people—one of the largest cave settlements in Europe.

Merino soon discovered that she was in an opal mining outpost called Coober Pedy. After a gold prospector discovered an opal in the area in 1915, miners flocked to the region to cash in. When soldiers returning from World War I joined the craze, they began living in dugouts excavated from the hillsides to escape the extreme daytime temperatures. It was a novel idea that stuck, and today much of the community of 2,000 lives underground. “The people there are so deeply connected to their environment,” Merino says. She stayed for a month, captivated by the unusual way of life.

A group of polygamist Mormons led by Enoch Foster (center) lives in more than 15 cave homes in Moab, Utah.

The practice of humans living in caves dates back millions of years to when our early African ancestors began taking refuge in underground caverns. Over time they became more than that—as people added rock art and held communal ceremonies, they became homes. After visiting Coober Pedy, Merino realized that in some places this ancient lifestyle still endures.

Much of life in Coober Pedy happens underground, including church.

In Moab, Utah, the Mormons’ homes, blasted out of the sandstone with dynamite 50 years ago, are kitted out with plumbing and electricity.

Exactly how robust these communities are is hard to quantify. In the early 2000s, some 30 to 40 million people lived underground in yaodong homes carved into the hillsides of Shaanxi Province in central China. But according to a 2010 estimate, that number had fallen to around three million as the population urbanized. Some communities have abandoned their subterranean homes entirely. In the 1300s, the Dogon people lived in caves along the Bandiagara cliffs in Mali to escape religious conquests and slave raiders, but over the centuries the threats receded and they abandoned their rocky abodes and moved into villages in the valley. Whatever the tally, it’s clear underground living is becoming increasingly rare.

Over the past two years, Merino traveled the world to seek out the remaining practitioners of this dwindling way of life to discover the advantages their enduring tradition provides. “The subterranean world is a continuous lesson in sustainability and circular economy,” says Pietro Laureano, a climate-focused architect and UNESCO consultant who’s studied cave populations. “It also teaches us a different symbolic relationship with space. Today we have forgotten the importance of the hidden, the unseen, the underground.” And indeed, from a small pocket of Mormon fundamentalists in Utah to a town of more than 3,000 in southern Spain, Merino found that while life in these communities seems more precarious than ever, they have much to teach us about human ingenuity and resilience.

The cave homes in the Sacromonte neighborhood of Granada, Spain, gave birth to flamenco more than 500 years ago. Today dancers such as Almudena Romero Álvarez, 45, perform for tourists in whitewashed grottoes each night.

Tocuato Lopez and his family have resided in the Guadix caves for four generations.

Part one: The holdouts staying cool as Tunisia heats up

For thousands of years, the Imazighen—also known as Berbers—in southern Tunisia have built their homes by chiseling into the low-slung sandstone hillsides that run through the wide plains of the Sahara. These cave shelters offered a cool escape from the searing heat and harsh desert winds. Then the national government suggested there might be a better way to live.

Fatma Haamdi, 73, prepares to take an afternoon nap in her sandstone home in southern Tunisia. Daily surface temperatures rise into the 100s, but the cave stays pleasantly cool.

It all started when Tunisia gained independence from France in 1956 and the new president, Habib Bourguiba, began pushing for the country to modernize, which meant moving cave-dwelling Imazighen into government-built housing aboveground. The people were promised cheap running water and electricity, though many who relocated soon found that wasn’t the case. “They lied to us,” says Slimen Ben Massoud, a 72-year-old who was born in a cave but moved to one of the government settlements in the 1970s. “They took everything from me and gave me nothing in return.”

Other attempts at relocation have been somewhat more successful. After a flood destroyed many of the homes around Matmata and Haddej in 1969, residents were offered land at nearby New Matmata for three dinars—a dollar—a square meter. For many, it was an offer too good to pass up. Today there’s one main road through the town, lined by a string of packed coffee shops, a butcher, and an arcade with a few gaming consoles set up in front of flat-screen televisions. But the town still fails to address the one problem the cave homes solved thousands of years ago: the heat. Tunisia, like much of the rest of the world, is heating up at an alarming rate, and temperatures are expected to rise by as much as 11.7 degrees Fahrenheit by the end of the century.

“You could have brought modernity to our traditions, but you can’t do the opposite,” says Ali Kayel, 59, at his empty roadside café, staring out over the moonscape of Haddej, where he was one of more than a thousand people born and raised in the hundreds of cave homes on the valley floor. He remembers how, when he was a child, the smell of food drifted between the caves, which would house two or three families each. People started to move away in the 1970s, and the area has been abandoned since the 1990s. Kayel says that the state never contemplated protecting his way of life, and many of those who moved out of the caves came to regret it.

In Matmata, Tunisia, Abdelafidh Krayem and his son take their goats back to a cave in the evening after an hour of grazing. In many cave communities, livestock live comfortably and safely in caverns adjoining a family’s living quarters.

Those who have stayed have found clever ways to meld the benefits of their ancient homes with modern living. Eight miles from New Matmata, the Haamdi family live in five rooms dug deep into the sandstone hillside of Beni Aïssa. Their home, one of just a dozen or so still occupied in the town, is accessed via an aboveground brick foyer that bakes in the Saharan sun, but the living areas beyond are comfortable and cool. A complex system of water channels and walkways, engineered over centuries, connects the two dozen homes pocked across the desert. When it rains, the channels flood gardens of palm, almond, and olive trees.

Inside, the Haamdis’ house looks much like any other 21st-century Tunisian home. The walls of a small pantry are adorned with shallots and garlic; the floors in the main living areas are lined with pillows and throw rugs. When eldest son Salem, 20, hooks up his phone to a copper antenna, the cave has patchy internet and Leila, 15, the youngest daughter, can record TikTok videos in a whitewashed storeroom. Grandfather Ali, 73, the family’s oldest member, was born in the cave and has lost count of how many generations came before him. “I will never leave here,” he says. Leila and Salem aren’t thinking of leaving either; they’re making plans to dig further into the porous rock.

(Descending into one of the deepest caves on Earth.)

Today we have forgotten the importance of the hidden, the unseen, the underground.

Pietro Laureano, cave expert

Part two: The tribe preserving a connection to the land in Jordan

The city of Petra was carved into the sandstone cliffs and canyons of the Jordanian desert over 2,000 years ago as the dazzling trading capital of the Nabataean empire. But for more than two centuries, Bedouin have called its labyrinth of catacombs, passageways, and chambers their home. It was a bucolic and pastoral existence—the slopes below the Royal Tomb were used for agriculture, and the tribe herded their goats through the long canyon into the city.

Hesen Ali Mohammad Semahin, 70 (at left), Raya Hussein Suliman Semahin, 90 (center), and Raya’s granddaughter Tamam Hussein Sallamh Semahin, 12, wait for water to be delivered to their home in a small cave settlement a short walk from Petra’s Royal Tomb.

It was the perfect spot until the 1970s, when the Jordanian government made plans to convert the site into an archaeological tourist attraction. King Hussein bin Talal brokered an agreement for the 140 Bedouin families to leave, and officials built towns nearby to house them. “Essentially, [it] was justified as preservation of the monuments, as well as establishing new employment and subsistence opportunities,” says Mikkel Bille, a professor of ethnology at the University of Copenhagen and author of Being Bedouin Around Petra. By 1985, most of the tribe had vacated the ancient city and Petra was named a World Heritage site.

The cave city of Petra, Jordan, was named a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1985 and is visited by hundreds of thousands of tourists each year. Bedouin have lived in this ancient sandstone city for centuries, and despite urging from the government, many don’t want to leave.

The Bedouin who remained, some 120 of them, were moved from the main archaeological areas to a peripheral valley, where tribe members have made use of whatever space they could find. What were once Nabataean tombs have become storerooms, and ancient halls now house tractors, pickup trucks, and camels.

Raya Hussein Suliman Semahin was born in the Royal Tomb when her tribe had free rein over Petra. Now age 90, she lives in a row of caves cut into the red rock of the adjoining valley: a kitchen with a wide firepit and blackened walls, a bedroom dimly lit by lights powered from a solar panel, and a wardrobe cave where her clothes and scarves are hung on a string suspended between two juniper tree branches.

On a dusty hilltop several miles from the valley, the government recently built a modern village with the intention of rehoming Petra’s remaining residents. Some cave dwellers are ready for a new way of life. Haniyah Suliman Ali Samahin, 37, wants her eight children to be closer to the school and have permanent access to fresh water, which currently trickles out of a tap on the valley floor just once every three or four days.

Others, though, will never leave Petra for a life of concrete and modernity. “We like the open air,” says 18-year-old Suleman Samahin, “the nature and the freedom.” As the sun sets, Suleman’s mother sits on a stone slab outside her cave home, tending to a fire. Nearby, Suleman and his brothers cook mansaf, a traditional dish of lamb and yogurt, in a sand-filled pit that once held Nabataean wine. When night falls, the family will lie outside on mattresses and animal pelts underneath the stars.

“Taking the Bedouin out of Petra is like taking the spice out of a dish,” says Raya. “You’re left with nothing.”

Part three: A home for the homeless in Lesotho

The cave at Ha Kome has always been a place of last resort.

In the early 19th century, a Basotho chief named Kome led his tribe into the Maloti mountains, fleeing a period of war that displaced millions of people throughout southern Africa and led to countless deaths. Kome came across a vast, east-facing cave surrounded by steep valleys and mountainous plateaus and set up camp. The location was “strategic for security reasons during those times,” says Joshua Chakawa, a senior lecturer in the Department of Historical Studies at the National University of Lesotho. Members of Kome’s tribe, he says, were able to shield themselves and, critically, their livestock from the violence.

During a period of war 200 years ago, Basotho chief Kome led his tribe to a cave in Lesotho’s Maloti mountains to protect them from the violence. They built huts from mud and dung underneath the lip of rock. Most of the tribal descendants now live in a village nearby, but the huts still provide shelter to those in need, like Ntefane Ntefane (at right), who can’t afford a village home and is visited here by a passing herder.

Eventually, the tribe built individual homes within the Ha Kome cave, molding six-foot-high domed huts from sticks, mud, and dung before smearing orange clay around the low doorways. Locals dubbed the cave the mahalapane—or palate—imagining it as a huge open mouth.

The Ha Kome cave huts in Lesotho don’t have electricity, running water, or windows. But they do provide a roof overhead for people like Sebastian Emisang Khuts’oane.

Khuts’oane raised his children in a cave home but moved to the nearby village five years ago. Now he uses the cave as a sort of guesthouse and stays there when relatives are in town.

At the turn of the 21st century, 33 of Kome’s tribal descendants still lived in the huts beneath the rock. Over the past two decades, nearly everyone has moved to a cinder-block village constructed on the bedrock above the cave, where the homes are basic but provide little comforts like glass windows and are more pleasant than the huts within a cave.

But the mahalapane is still a place of refuge and security for those in need. Ntefane Ntefane, a 41-year-old farmer, can’t afford to build a home in the village, so he lives in the cave, sleeping on a bundle of animal skins and washing his clothes in the Phuthiatsana River, which flows past the cave’s mouth. He sweeps the dust out of his house with a straw broom and shovels it into a small fire grate, where an old teapot sits over the flames. Inside, he has a few empty candleholders set on a shelf in the corner, and three leather suitcases are stacked beside buckets and washbowls.

Adjacent is Sebastian Khuts’oane, 58, who is using the one-room hut where he raised his children. It’s a quick solution to a temporary problem: His daughter-in-law is visiting from South Africa, and he’s given her and her family his home in the village.

You May Also Like

The men wake each morning with the sunrise, as copper-pink light bathes the rock. The only shade comes from a lekhatsi tree, a variety of wild peach, which, according to local lore, was planted two centuries ago by Kome to ward off lightning strikes.

Locals call Ha Kome cave the mahalapane—or palate—picturing the overhanging rock as an enormous open mouth.

Soon Khuts’oane’s daughter-in-law will head back to South Africa, and he’ll move up to the village. And Ntefane says he’ll build a house of his own when he can afford it. Until then, they make do with their home beneath the mahalapane.

(Cave ecosystems thrive in the dark. What happens when tourists light them up?)

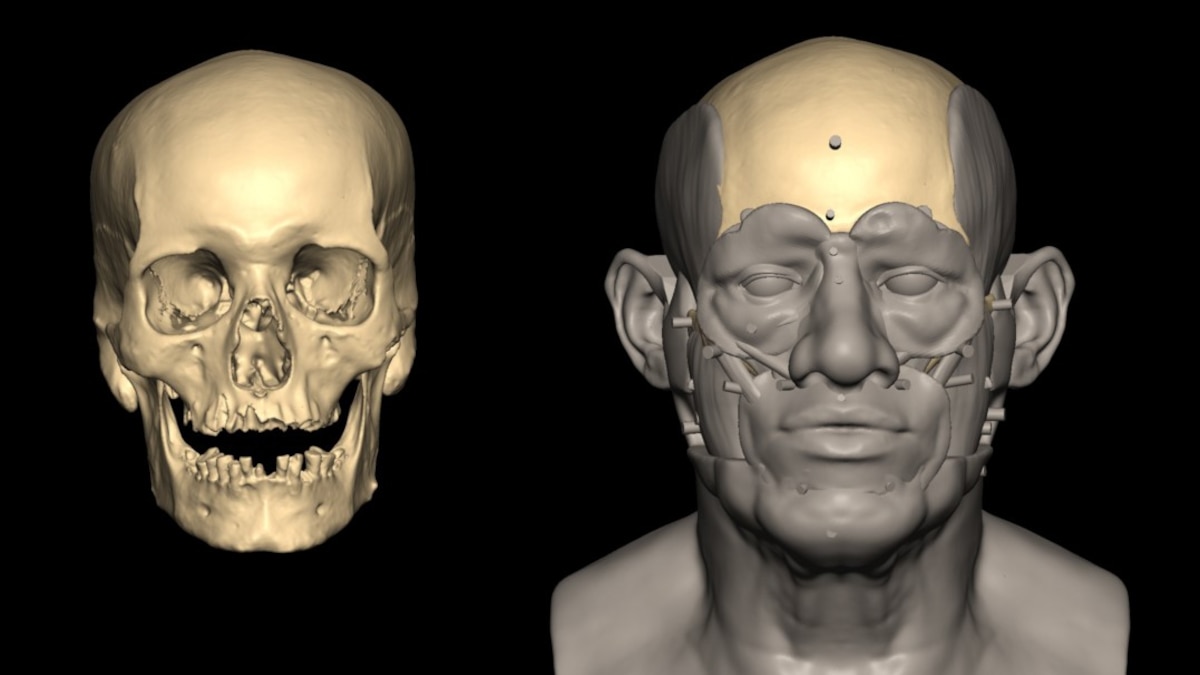

Part four: The dwelling in Turkey that checks all the boxes

The volcanic landscape of Cappadocia, in central Turkey, has eroded over millennia to form mountain ridges, sandstone valleys, and rows of Gaudiesque cones that the tourism industry likes to call fairy chimneys. Over 4,000 years, humans, too, have carved the porous rock, excavating a warren of caves, tunnels, and passages. Among 205,000 acres of archaeological sites in the region, there are dozens of abandoned underground cities. One, Kaymaklı, is over 4,000 years old and extends eight stories belowground, complete with stables and wine cellars. Another, Derinkuyu, was vast enough to have housed 20,000 people at once.

Homes in Turkey’s Cappadocia region have been carved from the porous sandstone for thousands of years. Oktay Torun (second from right) and his wife, Hanife (right), have lived in one such dwelling in the town of Ortahisar since they were married four decades ago. But tourism in the area is booming, and many of the Toruns’ neighbors have sold their cave homes to developers catering to visitors.

While these larger archaeological treasures haven’t been occupied in more than a hundred years, many of the individual homes carved into the area’s rocks are still in use. Oktay, 72, and Hanife Torun, 64, have lived in their cave home in the hilltop town of Ortahisar since their wedding day more than four decades ago. They are one of maybe 10 families left living full-time in a cave in all of Cappadocia, and they love it for a simple reason: It satisfies all their needs. The home has plumbing and electricity. The living room stays warm enough in winter, while the adjoining storage room, separated by a thick rock wall, maintains a stable, cool temperature that allows them to eat summer crops all year round. Rows of amphorae hold bulgur and lentils harvested five seasons ago, and walnuts and fresh fruit are stacked on silver trays.

While the Toruns have always seen the value in their cave home, the rest of the world has started to take notice too—nearly five million people visited Cappadocia in 2023. This tourist boom has prompted many locals to convert their cave homes into shops and hotels, and ancient storehouses into underground restaurants and bars. Recently, one of the Toruns’ neighbors sold his cave to hotel developers, leaving the couple completely surrounded by tourism projects. Now when they duck into their cave, they’re met with the low throb of a drill shaking the floor and trails of fine dust dropping from the ceiling.

(Why the cave cities of Turkey’s Cappadocia are best explored on foot.)

People have been digging into the soft sandstone in Göreme, Turkey, for centuries, forging homes, churches, and stables. It’s now the tourism capital of Cappadocia, and the old homes have been converted into hotels.

Oktay and Hanife’s son, Rıfat, 45, grew up playing hide-and-seek in the maze of carved churches and catacombs beneath the family home. Now, like almost everyone here, he works in the hospitality industry, driving visitors from all over the world from one attraction to the next.

The steady advance of tourism in Ortahisar is likely to force the family out before too long. “If we have to leave, we will sell everything and end up living just like everyone else,” says Hanife, tears welling in her eyes. Many of those who’ve moved out of the caves around Cappadocia have ended up in the city of Nevşehir, where squat apartment blocks with double-glazed windows and enclosed balconies crowd basketball courts and shops. “Living in an apartment is like a jail,” says Hanife, as she rushes about her house filling bowls with fruit and vegetables from the storerooms. While she skins a plait of green onions onto a tray, fresh milk from the family’s two cows bubbles on a stove to make cheese. “When I open the door, I need to breathe fresh air and see the valley.”

(This U.S. national park has the world’s longest cave system—and an unusual history.)

A version of this story appears in the August 2025 issue of National Geographic magazine.

The nonprofit National Geographic Society, committed to illuminating and protecting the wonder of our world, funded the work of National Geographic Explorer and photographer Tamara Merino. Learn more about the Society’s support of Explorers.

Based in Santiago, Chile, Tamara Merino photographed cave-dwelling communities in seven countries, including Lesotho and Tunisia, for this story on what she calls “humanity’s first homes.” Her work has also appeared in Time, the New York Times, and Libération.