Now Reading: A tree fell in the Amazon—and revealed mysterious urns of ancient human remains

-

01

A tree fell in the Amazon—and revealed mysterious urns of ancient human remains

A tree fell in the Amazon—and revealed mysterious urns of ancient human remains

When a massive tree toppled in the floodplains of Fonte Boa, a region in the Brazilian Amazon, local fishermen noticed something odd: The roots had hoisted two giant ceramic pots above ground. Nobody knew what they were or who had buried them. In June, the Brazilian government announced that archaeologists had identified the pots as funerary urns—possibly going back millennia—from Indigenous groups who inhabited the region before the Portuguese first arrived in Brazil about 500 years ago.

Excavations revealed seven urns—some fragmented—entangled among the tree’s roots, containing human bones. The largest stretched almost three feet in diameter and weighed about 770 pounds, says Márcio Amaral, an archaeologist with the Mamirauá Institute in Tefé, Brazil, who helped lead the excavations. “We needed a whole day to loose this large one free from the roots and six men to move it from there,” he adds.

Removing the urns from the ground and transporting them to the Mamirauá research lab in Tefé for study was a complex process. Walfredo Cerqueira, the community leader who mobilized his fellow fishermen to help in the excavations, recalls the unusual experience: “We thought we’d get there with hoes and move things around easily, but from what I had seen of how archaeologists work on TV, I knew it would be slow work.”

The tree fell in an area known as Cochila Lake, an archaeological site in the Middle Solimões river region. It is one of more than 70 artificial plains in the area built around 2,000 years ago by Indigenous groups to avoid floods during the river’s high-water season. “Given how little we know about [the past of] this region and how difficult it is to get there, this is really an unprecedented find,” says Karen Marinho, an archaeologist with the Federal University of the West Pará (UFOPA) who did not take part in the excavations.

Last October, locals in the Amandarubinha community saw the toppled tree and contacted a local priest who reached out to the Mamirauá Institute, more than 150 miles away. With community help, archaeologists from the institute excavated the urns earlier this year.

Photograph by Geórgea Holanda, Mamirauá Institute

The urns don’t match artifacts previously found nearby—and for now, they raise more questions than answers.

(How long have humans been living in the Amazon?)

What we know about early Amazon pottery

Pottery has a long history in the Amazon, and it’s one of the few types of artifacts to survive in a damp, hot environment that’s not ideal for archaeological preservation.

Archaeologists from the Mamirauá Institute worked alongside community members to excavate the urns.

Photograph by Geórgea Holanda, Mamirauá Institute (Top) (Left) and Photograph by Geórgea Holanda, Mamirauá Institute (Bottom) (Right)

The first known human occupations of the Amazon region created ceramics in the Pocó-Açutuba tradition, dating between 1500 B.C. and A.D. 200. Ceramic containers in this tradition are richly decorated with different types of carved patterns. Next, came the Borda Incisa tradition, mainly characterized by cuts along the edges of ceramic vases and containers. Finally, from the fifth to the 16th centuries, the Polychrome ceramic tradition incorporated dyes in different colors, especially brown, red, black, and orange over a white or gray background.

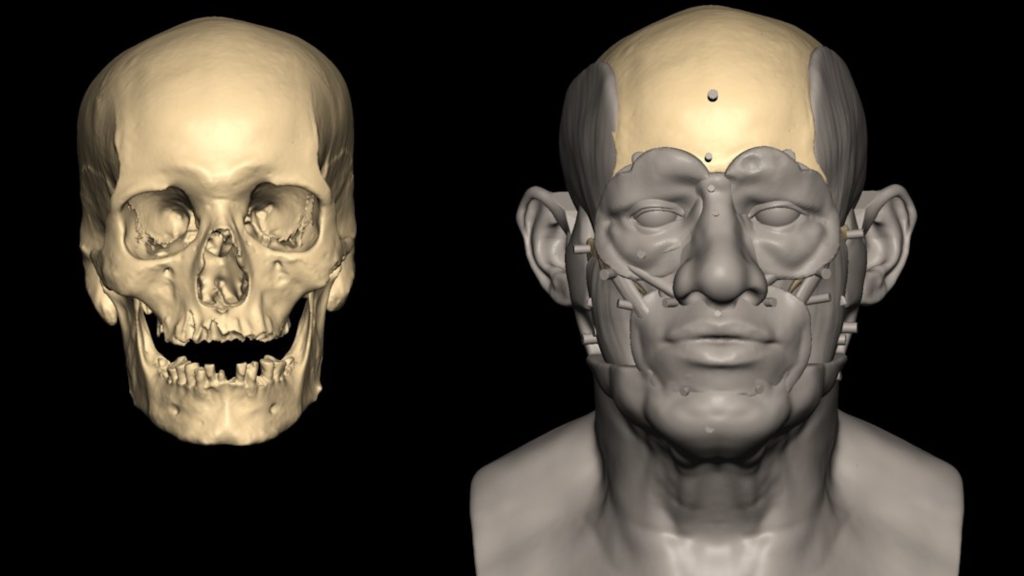

The urns do not seem to belong to any of the ceramic traditions known in the Middle Solimões or in the broader Brazilian Amazon. “This is a type we haven’t got records of yet,” Amaral says. The absence of ceramic lids set the new discoveries apart artistically. These funerary urns are also rounder than those produced in known styles, notes Anne Rapp Py-Daniel, an archaeologist with UFOPA who did not take part in the research.

You May Also Like

How did ancient Indigenous people bury their dead?

The richness of the craft that turns these urns into pieces of art says much about how ancient Indigenous communities related to death in the Amazon. To these groups, “death is a process, not a moment,” Py-Daniel observes. It is another rite of passage that involves effort and dedication from the whole group, especially if the deceased member had an important role in it.

Some of the urns were up to three feet wide and required extra effort to remove them from the tree’s root system. Here the team works to remove one of the urns.

Photograph by Geórgea Holanda, Mamirauá Institute

Putting bones within ceramic containers, Py-Daniel explains, would have been part of a second step in the funerary process. First, the departed must undergo a ritual to remove flesh, through burial, cremation, or submersion in a river—where the body is wrapped in a woven net that allows fish to feed on it. Then the bones are carefully collected and arranged to, in another ritual, be placed inside the urn. “Indigenous groups who did not have their traditions obliterated by the presence of missionaries still [entirely or in part] follow this ritual,” Py-Daniel says.

Throughout the Amazon, many groups once buried such vases with their dead beneath their houses (and some still do), says archaeologist Geórgea Holanda, who led the excavations with Amaral. “On social media, many people ask us how a tree could have grown on top of the urns,” she says. “The tree probably grew after the people who used to live in that region were gone.” As the tree grew, its roots made their way into the pots possibly drawn to nutrients in the bones, Holanda adds. While the tree’s exact age remains unknown, its size suggests it could be centuries old, and the researchers suspect that the vases are even older.

(Here’s why a once isolated tribe took up cell phones and social media.)

Community-driven archaeology

For now, the exact age and origin of the urns remains a mystery. The presence of fish and turtle bones around some of the ceramic fragments also raises questions. “We still have to… find out what these leftovers are—whether they were part of an associated ritual,” Amaral says.

Researchers at Mamirauá are currently cleaning and excavating sediments from within the urns while they look for funding to study the material. Ultimately, they hope to carbon-date fragments of bone and coal to get a more precise age estimate. “It will all depend on funding and the partnerships we can get,” Holanda stresses.

Even with these unknowns, Amaral and Holanda both feel that the most important aspect of the discovery was the deep involvement of locals from the Arumandubinha and Arará villages, who helped the archaeologists plan every single step of the process. “The demand came from them, as they wanted to know what these artifacts were—otherwise we’d never know about the urns,” says Amaral.

Community members helped build special scaffolding to remove the urns without doing further damage and guided the researchers on the best time to excavate. “It all would have been impossible without them,” Holanda says.