Now Reading: Marathi Grammar Guru Shatters Myths at 100

-

01

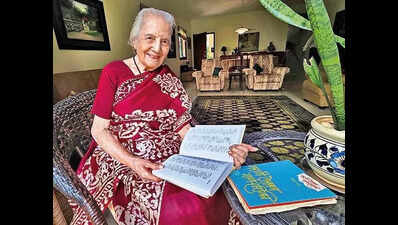

Marathi Grammar Guru Shatters Myths at 100

Marathi Grammar Guru Shatters Myths at 100

During the last census in 2011, the surveyor who showed up at Yasmin Shaikh’s doorstep did what people often do when they hear her name—he assumed. “Urdu,” he wrote in the mother tongue column without asking.

“My mother tongue is Marathi,” Shaikh demurred.Seated at her dining table just days after turning 100, the grammar veteran laughs at the memory. “The surname and I have had a long journey,” she says, recalling how a builder once backed out of a flat deal on hearing her name. Another time, a co-passenger on a train—whose kid had bonded with her over a crossword—got up “as if something bit her” when Shaikh introduced herself.Clad in a floral pink gown this rainy afternoon, her trusty walker—”my companion”—and well-wisher Dilip Phaltankar by her side, Shaikh shows no sign of age slowing her down. She writes by hand, reads fine print without glasses, and recalls details like the name of a wartime English periodical printed “only in India”: Gestapo.

Born Jerusha Reuben in Nashik on the midnight of June 21, 1925, she was the second of seven children in a Marathi-speaking Jewish household.

Her home brimmed with Marathi novels by Nath Madhav and H N Apte, along with magazines like Stree. “They were kept in trunks. I loved opening them to read,” she says. When her mother, Ruth, died suddenly, nine-year-old Jerusha escaped into fiction even as the voice of Kumar Gandharva wafted from the gramophone.

“My father, John, had an ear for music.” At her Marathi-medium school in Pandharpur—where her father was posted—a teacher named Talekar made grammar feel simple and magical.

Later, in 1942, after a move to Karad, she insisted on studying further and found herself the only Jewish student at Pune’s SP College, where her sari-clad presence turned heads. The year she began pursuing a BA in Marathi, two new subjects were introduced: Linguistics and Grammar.

A fan of writers such as V S Khandekar, she wrote stories for the college magazine. Encouraged by her professor S M Mate, she topped not just her class but the college.

After a brief stint teaching in a primary school, she returned to do her MA. Post-Independence, Jerusha began teaching in a girls’ school in Nashik, where she heard about a theatre manager called Daddy Shaikh from Marathi writer Vasant Kanetkar. Expecting an elderly man, she was surprised to meet Aziz Ahmed—young, strapping and, to her, instantly captivating.

“My father was opposed to the match. Jews and Muslims have a chequered history.”

But she stood her ground. Three days after the Indian constitution came into force, the couple married in court. “There was no pressure to convert. The in-laws were progressive. The sister-in-law, Zubeida Shaikh, was India’s first Muslim woman MBBS,” says Phaltankar, co-author of Shaikh’s gaurav granth—a book of honour marking her century. “While registering our marriage, we took an oath: ‘I belong to no religion’,” says Shaikh, who changed only her name after marriage.Sion’s SIES College was still under construction in 1962 when Marathi department head S P Bhagwat offered her a teaching post. By then a mother of two, Shaikh moved with her family to Chembur. On her first day, students expecting a burqa-clad professor were stunned to see a woman with permed hair in a sari. During the 1965 Indo-Pak war, six students shouted “Pakistani” as she entered a lift. “I complained to the principal.

He scolded them,” recalls Shaikh.Maharashtra was a toddler when she became a member of the Marathi Sahitya Mahamandal, a committee formed to formalize Marathi grammar. When the committee came up with 18 grammatical rules and guidelines by 1972, Shaikh wrote a book demystifying these principles. Invited to teach Marathi grammar to IAS aspirants after retiring, her classroom spawned names such as Mumbai’s municipal commissioner Bhushan Gagrani and Pune-based income tax commissioner Sangram Gaikwad.

“Their progress is my real inheritance,” she says, as Phaltankar shows a letter of gratitude from Gagrani. “Even when her husband was in the ICU in 2002, she didn’t miss the deadline,” says Bhanu Kale about the centenarian who proofread his monthly magazine ‘Antarnaad’ for 15 years. Sleepless after her husband’s demise, Shaikh buried herself into the nitty-gritty of matras and anusvars. Even today, typos gnaw at her like pebbles in a rice plate. “I can’t help it,” frowns Shaikh, who spends hours reading and responding to grammar queries from across the world.

We ask for an autograph. It says in Marathi: “Love your mother tongue.”