Now Reading: Scientists Discover Gene Giving Aussie Skinks Snake Venom Immunity

-

01

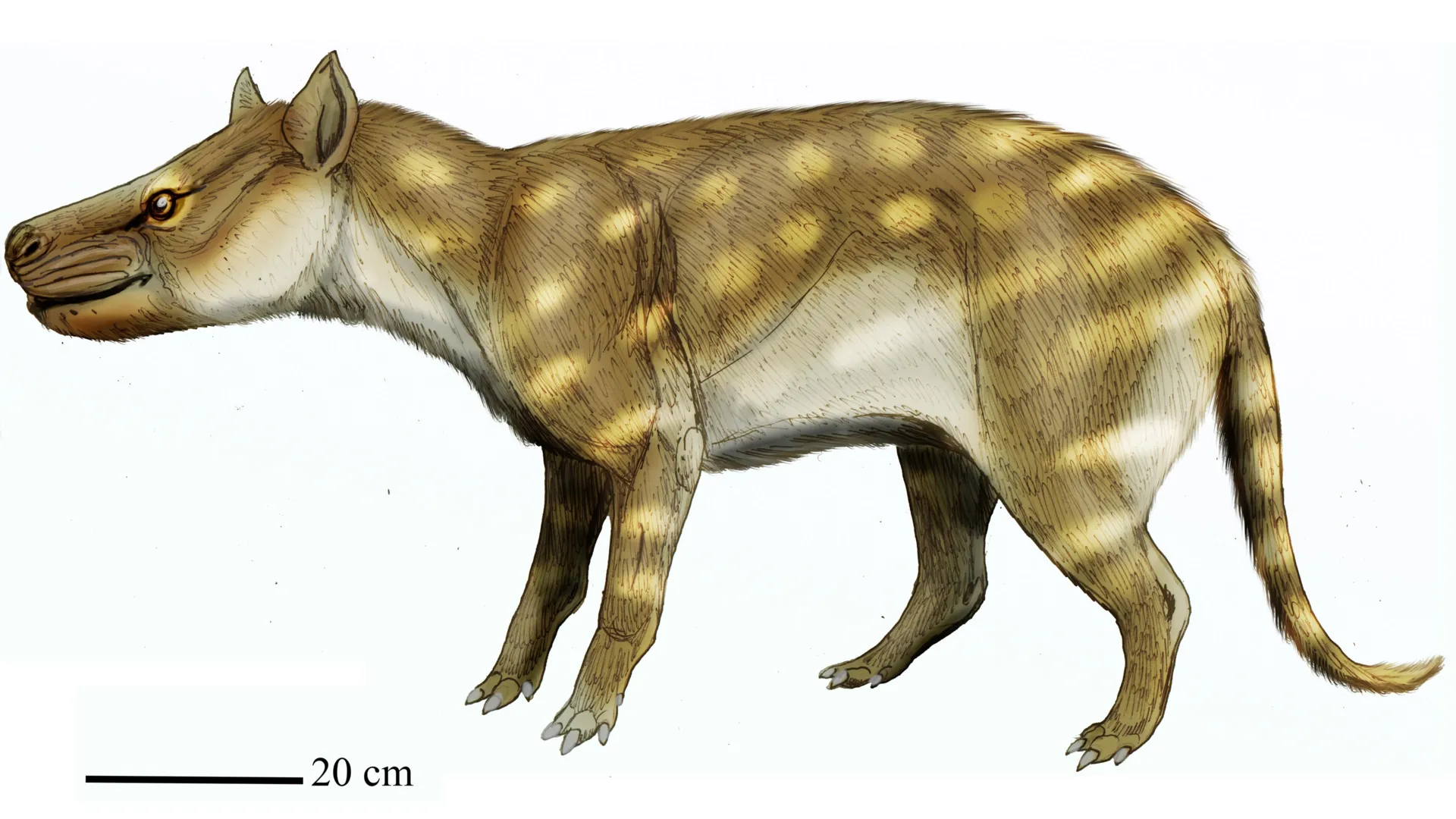

Scientists Discover Gene Giving Aussie Skinks Snake Venom Immunity

Scientists Discover Gene Giving Aussie Skinks Snake Venom Immunity

Fast summary

- A University of Queensland-led study discovered Australian skinks have evolved resistance to snake venom through molecular adaptations.

- The evolution centers on changes in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, targeted by neurotoxins to block nerve-muscle communication and cause paralysis.

- Skinks developed mutations at binding sites on the receptor that prevent venom attachment,independently occurring 25 times across evolutionary history.

- Similar resistance mutations were observed in other animals like mongooses and honey badgers, showcasing convergent evolution.

- Mechanisms include adding sugar molecules to physically block toxins and substituting a protein building block (amino acid arginine at position 187).

- Laboratory testing confirmed modified receptors in skinks effectively resist venom effects.

- Researchers hope these findings can guide biomedical innovations for antivenoms or therapeutic agents against neurotoxic venoms.

- Published in International Journal of Molecular Sciences, with contributions from museums across Australia.

Indian Opinion Analysis

while this research focuses on Australian skinks, its implications resonate globally, including for india. Snakebite-related fatalities remain a important public health concern in the country-especially among rural populations. Insights into how nature counteracts neurotoxic venoms might play a crucial role in advancing next-generation treatments or antivenoms tailored for India’s diverse array of venomous snakes. The study also underscores the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration between evolutionary biology and medical research to tackle real-world issues. As biodiversity continues to be explored scientifically, such discoveries may pave paths toward saving lives by learning from evolutionary resilience mechanisms seen across species.