Now Reading: Supreme Court allowed cities to ban camping. Here’s what happened next in California.

-

01

Supreme Court allowed cities to ban camping. Here’s what happened next in California.

Supreme Court allowed cities to ban camping. Here’s what happened next in California.

In the year since the U.S. Supreme Court made it easier for cities to remove homeless encampments, California cities have redoubled enforcement efforts.

The court ruled last June in City of Grants Pass v. Johnson that it was not cruel and unusual punishment to outlaw camping in public spaces. Over the past year, cities have removed makeshift shelters from sidewalks and city parks, regardless of whether they have shelter beds available. Complicating matters, the state of California is facing a $12 billion deficit. Last year it allocated $1 billion toward helping cities house homeless residents. This year, lawmakers have zeroed out the main source of funding in the budget.

For people caught up in sweeps in cities like Berkeley, Oakland, and Vallejo, the same question echoes again and again: “Where do I go now?”

Why We Wrote This

The Supreme Court ruled on June 28, 2024, that banning camping for homeless people did not constitute cruel and unusual punishment. In the year since, California’s cities and its homeless population have navigated a new legal landscape.

For now, Evelyn Davis Alfred doesn’t have to go anywhere.

On a patch of vacant city-owned land in Vallejo, Ms. Alfred waters the succulents outside her tent shelter as neighbors come to greet her with groceries and more plants.

Over the course of two years, Ms. Alfred built a shelter she calls her “bungalow,” complete with a shower, raised bed, and front yard. She’s beloved by her neighbors and says her bungalow offers a sense of security while she waits for permanent housing. She has applied to 19 places and has been waiting almost two years for an opening.

She had a mailbox, too, until the city came to evict her last October. Like many cities, Vallejo has a long-standing ban on camping on public land.

“I got a notice that I had 72 hours, but they came before then,” says Ms. Alfred through tears, outside her bungalow. “They wanted me to pack up everything and move, and I couldn’t do that. There’s no way, not in my condition.”

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

Evelyn Davis Alfred has lived in this tent in Vallejo, California, for two years. She has sued the city to remain under the Americans with Disabilities Act and the 14th Amendment.

Her eviction came months after the June 28, 2024, Supreme Court ruling. Ms. Alfred, an older woman who is disabled, couldn’t leave.

“There’s been more enforcement than ever since they made this rule that we can’t camp anywhere,” Ms. Alfred says. “Where do they want us to go? There’s nowhere to go.”

So she sued. And in February, a district court judge blocked the city from dismantling her bungalow until her case is resolved, citing concerns about her safety.

Ms. Alfred’s lawyers claim the city of Vallejo violated her rights under the Americans with Disabilities Act and the 14th Amendment’s state-created danger doctrine. Ms. Alfred is represented by Where Do We Go Berkeley, a nonprofit that offers free legal defense and legal aid all over California. The judge sided with Ms. Alfred, writing that if the city knowingly put her in danger, that could violate her right to due process protections.

The 14th Amendment prohibits states from depriving any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law. The state-created danger doctrine is a legal principle under that amendment, arguing that the state’s actions, in creating or increasing a danger, violate this right.

Ms. Alfred’s advocates say her case represents a new legal foothold for homeless people and their advocates after the Supreme Court’s 6-3 decision last summer.

There have been more lawsuits challenging sweeps under the Americans with Disabilities Act and both the Fifth and 14th Amendments, says Laura Riley, a University of California, Berkeley law professor.

“There’s a tendency to forget that these laws and these legal protections apply to everyone, including people who are unhoused,” says Professor Riley. Almost 50% of people experiencing homelessness live with some type of disability, according to the National Institutes of Health.

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

A sign is shown outside Evelyn Davis Alfred’s tent home.

As Ms. Alfred’s case awaits a hearing, Ms. Riley says a verdict would “give the legal community some insight into whether courts are receptive to other approaches outside of the Eighth Amendment.”

Previously, advocates used the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment. Since the Grants Pass decision, 42 California cities and two counties have passed some version of a public camping ban, according to the National Homelessness Law Center. Most prohibit sleeping or storing property on public land, and carry fines or jail time.

Vallejo City Manager Andrew Murray says the city’s approach to encampment sweeps is evolving.

“We’re kind of driving the car while fixing it, too. We have no other choice,” he says, adding that in addition to pausing sweeps, the city hired a consultant to help develop a long-term strategy.

“Providing housing to the unhoused is not a traditional municipal function,” Mr. Murray says. “Cities in particular are in a challenging position because they’re not traditionally responsible for these types of social and health issues.”

The city’s two main housing projects for homeless people – a new 125-bed shelter and a 47-unit permanent housing complex Mr. Murray says is due to open later this summer – met with delays and increased expenditures. The new Navigation Center, a “one-stop shop” for services and case management that opened this month, took nearly a decade to complete.

“We’re in the same position as many other communities,” Mr. Murray says. “We all have a role to play. But there certainly needs to be a multilevel commitment and effort because cities alone don’t have the resources.”

“No more excuses”

Homelessness in the Golden State reached a record high of 187,000 people in 2024, driven by rising rents, stagnant wages, and a severe housing shortage.

In May, Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom urged cities to ban camping “without delay.” “No more excuses,” he said at a news conference that also announced $3.3 billion in funds to help house people. “It is time to take back the streets. It’s time to take back the sidewalks.”

His proposed model ordinance bans staying in one spot for more than three nights, building makeshift shelters, and obstructing sidewalks.

Dr. Margot Kushel, director of the Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative at the University of California, San Francisco, appreciates the boost in state funds for housing but remains skeptical of the governor’s model ordinance.

“The biggest problem with criminalization is not a moral problem. … It’s just purely that criminalization worsens homelessness,” says Dr. Kushel.

Encampment sweeps often harm residents’ health, disrupt access to services, and derail progress toward stable housing, according to the National Health Care for the Homeless Council.

From 2019 to 2024, the state spent $24 billion to reduce homelessness. During that time, the number of people without housing grew by 30,000. A 2024 state audit found that California’s efforts were undercut by poor coordination. The California Interagency Council on Homelessness failed to track costs and outcomes after 2021, and progress remains difficult to measure.

“The public should hold those policymakers accountable and say, ‘Why are you taking expensive efforts to worsen a problem?’” says Dr. Kushel. “This problem is 40 years in the making.”

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

Kimberly Griffith was evicted from her tent home on East 12th Street, where she was living for about seven months, in Oakland, California. When the city came to sweep the area, she thought she was getting housed, as she had signed up to get housed. But her name wasn’t on the list.

What happens after a sweep

In Oakland, where homelessness remains a highly visible crisis, state-funded efforts to move people from large encampments into hotel shelters show some progress. The city’s most recent homeless census counted 5,485 homeless residents in 2024 – about 67% of them unsheltered.

At a recently cleared encampment on East 12th Street, Trey Torres and Kimberly Griffith pack their belongings into a collapsible camping wagon, not knowing where they would sleep that night. They had lived there for months and thought help had arrived when outreach teams showed up.

“The day they came, I thought we were getting housed,” says Mr. Torres. Instead, he was given less than 30 minutes to leave.

Most at the site, which housed 70, were relocated to a hotel shelter. Mr. Torres and Ms. Griffith say they weren’t accepted and don’t know why.

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

Huy Pham, who has been homeless since 1995, sits on the land where he used to live on East 12th Street before it was cleared by the city in Oakland, California. Mr. Pham signed up for the city’s hotel shelter, but when he arrived, his name wasn’t on the list.

“Imagine having to move 200 feet every three days, 100 times a year, because you’re poor,” says Professor Riley, assistant dean of clinical education at Berkeley Law, referring to the state’s model ordinance. “Constant displacement is no recipe for compassion.”

She says there’s little to suggest that punitive measures reduce homelessness – they merely push it out of public view. As California ramps up enforcement, she worries that it may redirect funding from permanent housing toward more temporary shelters or even the criminal justice system.

With growing pressure to “clean up” encampments, cities risk swapping long-term solutions for short-term optics, she says.

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

Activist Yesica Prado checks in with homeless people living in Ohlone Park in Berkeley, California. Ms. Prado is homeless herself. She is also the founder of the Berkeley Homeless Union and brought a lawsuit against the city.

Torn between safety and compassion

In Berkeley, the balancing act between safety and compassion plays out daily at Ohlone Park.

Nicholas Alexander walks his dog through the park most mornings. Lately, it has felt less like a neighborhood refuge and more like a public health concern.

Once called “Everybody’s Park,” the five-block greenway was renamed in the 1970s to honor the Indigenous Ohlone people. Today, it has become a flash point in the debate over homelessness.

Over the past six months, at least 40 people have set up tents, angering neighbors who are fed up with daily disruptions such as shouting matches, open drug use, and off-leash dogs. They say their repeated calls to the city have gone unanswered.

“This camp needs to be swept because the entire Ohlone Park has changed for the worse,” says Mr. Alexander, standing beside the chain-link fence dividing the encampment from the dog park. “We’re not anti-homeless – we’re anti this behavior,” pointing to three unleashed dogs that had just chased a runner and two Monitor journalists.

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

Nicholas Alexander, with his dog, Hera, is part of the Save Ohlone Park group, in Berkeley, California. He was formerly homeless himself.

Mr. Alexander, who himself was formerly homeless and lived at an encampment, says Ohlone Park is getting worse by the day.

“The difference is, we had a stronger sense of community and roles,” he says of his time being homeless more than 10 years ago, when he helped feed dozens of residents. “This camp has none of that.”

He’s part of Save Ohlone Park, a group pushing for more shelter options and safety measures. But some neighbors say they have grown too exhausted for long-term fixes, willing to accept short-term solutions if it means the park feels safe again.

“I get that there aren’t any good solutions,” says Mr. Alexander. “But at what point do behaviors get so bad that we can sweep without offering resources?”

Roderick Simpson lives in a tent nearby and knows neighbors want the encampment gone. He thinks it’s ironic how quickly people forget that homelessness is rarely a choice.

“That guy was homeless, too. Now he yells at us from the dog park,” Mr. Simpson says of Mr. Alexander.

Mr. Simpson shares the neighbors’ concerns about the disorder, but says Berkeley’s sweeps have forced too many people with different needs to Ohlone.

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

Local residents attend a town meeting about the homeless encampment in Ohlone Park in Berkeley, California.

“It just makes everybody else look bad,” he says. “There’s a lot of us here that actually work or are trying to figure it out.”

At a crowded community meeting in May, City Manager Paul Buddenhagen called homelessness the “single hardest issue” the city faces. “It’s a humanitarian crisis, but it’s also impacting everyone.”

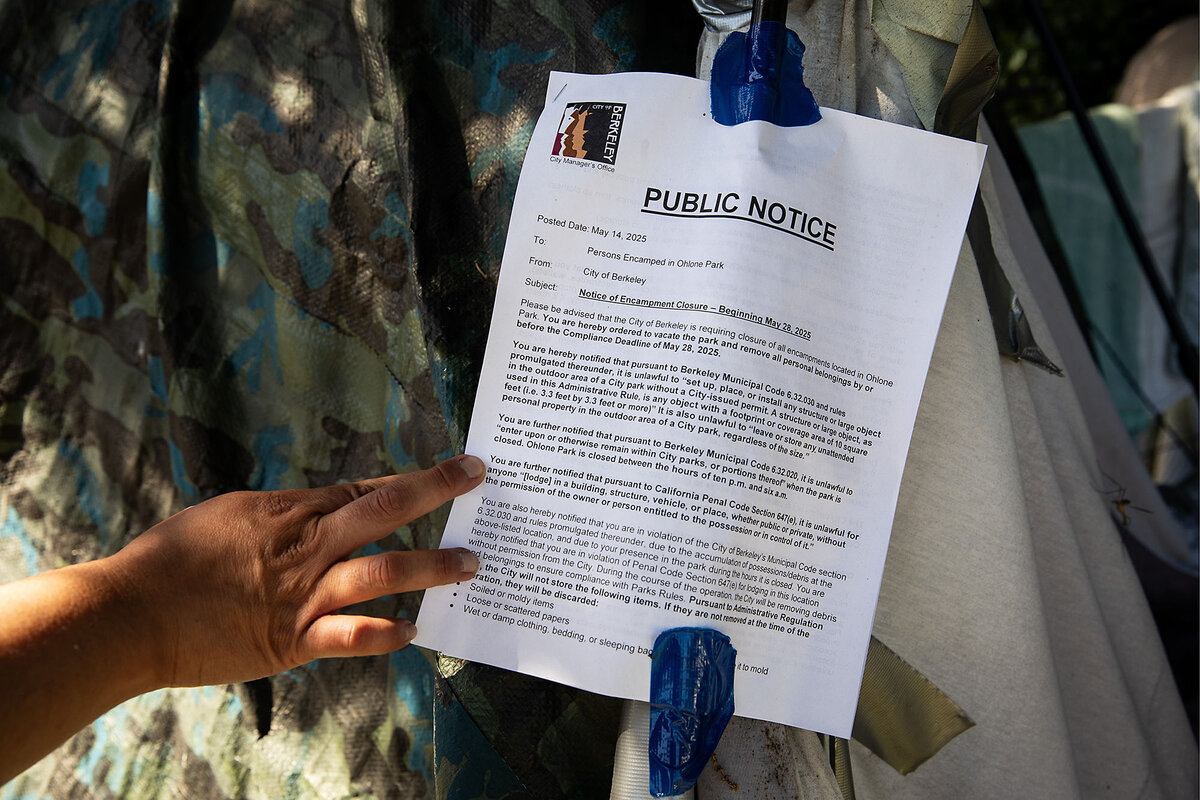

The city posted eviction notices at Ohlone Park. But another lawsuit – this one from the Berkeley Homeless Union – threatens to stall the sweep. It would be the seventh time Berkeley has been sued over an encampment closure.

Berkeley officials say lawsuits have become expected in encampment clearings. Still, they say they’re not just shifting tents.

“We’re not interested in kicking encampments from one street corner to the next,” said Peter Radu, manager of the city’s Neighborhood Services Division. “That doesn’t solve the problem. It just recycles it.”

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

An eviction notice is posted on a tent at a homeless encampment in Ohlone Park in Berkeley, California. The city planned on sweeping the area at the end of May.

Since 2021, Berkeley has reduced unsheltered homelessness by 45%, one of the steepest declines in the Bay Area. The city spent over $80 million in local and state funds to add 164 units of permanent and interim housing. Nearly two-thirds of those contacted by the city’s Homeless Response Team have moved into housing. But local funding approved by voters is drying up.

“We just don’t have the funds to keep the lights on, let alone expand,” said Mr. Radu, who is also pushing for more local control over who gets housed. At the Step Up Housing site – 82% funded by Berkeley – the county decides who gets in. “We have no say,” he says.

He also noted the city of 118,000 is carrying a regional weight. Only 57% of those surveyed in Berkeley’s homeless census were last housed in Alameda County. “We’re shouldering more than our share,” says Mr. Radu.

He believes the city’s model is effective, if it can survive the budget cliff.

“What we’re doing works,” says Mr. Radu. “We just need a way to keep doing more of it.”